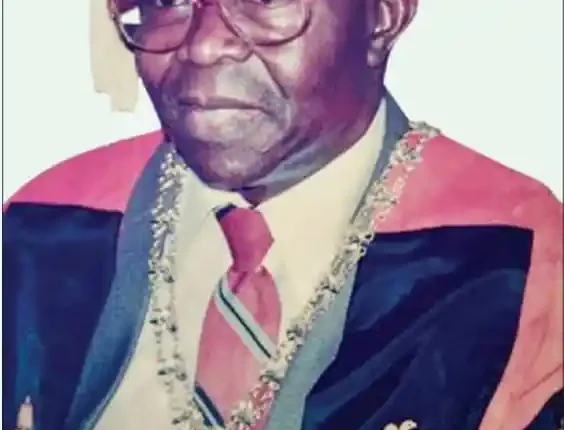

Theophilus Oladipo Ogunlesi: Biography of the First Nigerian Professor of Medicine

- Advertisement -

By Abraham Ariyo, M.D.

Professor Theophilus Oladipo Ogunlesi was born on July 12, 1923, and died on January 19, 2023, in Sagamu, Western Nigeria. He was 99 years old. He became the first Nigerian Professor of Medicine from 1965 until he retired in 1983. He was Professor Emeritus of Medicine from 1983 to 2023 at Nigeria’s Premier Medical School, The College of Medicine, University of Ibadan. We celebrate his life this week.

Young Ogunlesi attended St. Paul’s Primary School in Sagamu (1930-36) and his Secondary Education at C.M.S. Grammar School in Lagos (1936-40). He was a precocious child nicknamed “professor” by his elementary school teacher.

- Advertisement -

Also Read

Chimamanda Adichie Biography, Net Worth, Letter To Biden, Personal Life, Controversies

Wole Soyinka biography, age, books, children, recent controversies

- Advertisement -

Ivara Esege Biography: All You Need To Know About Chimamanda’s Husband

He distinguished himself and leapfrogged many grades because of his exceptional abilities. He entered Pre-Med at the Yaba Higher College (1941-42) and subsequently attended the historic Yaba Medical School (1942-47). He qualified as a Licentiate in Surgery and Medicine (L.S.M.) in 1947. Although L.S.M. was a legal certificate to practice Medicine in Nigeria, holders were looked down upon by physicians that attended University Medical Schools with M.B.B.S. degrees. In 1948, Yaba Medical School was abolished, and the University of Ibadan Medical School was started with official Medical degrees issued by the University of London. Thus, a significant conundrum existed among the L.S.M. holders who did not fit well into the new system, as one used the term “fish out of water.”

From 1947-49, Nigerian Hospitals did not accept L.S.M. holders as Medical officers. Thus, Young Ogunlesi worked as an Assistant Medical officer, shuffling from community clinics and public health facilities, a period he described in his own words as “turbulent years.” In 1948, during this turbulent period, a ray of hope shone through this darkness when one of the L.S.M. seniors took and passed the Conjoint Examinations in Edinburgh – the first time an African would pass this exam, opening doors for other L.S.M. candidates. Further, in 1951, the same candidate took and passed the coveted membership examinations of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Edinburgh – the first African to pass any Royal College of Physician membership. This news spread like wildfire, giving renewed hope to the disenfranchised L.S.M. holders like Ogunlesi, who were still in turbulent times.

- Advertisement -

In 1950, Young Ogunlesi also went to the United Kingdom, took the conjoint exam, and passed, a move that solidified his L.S.M. certificate and allowed him to get a job as a Medical Officer like a bonafide physician with an M.B.B.S. degree. He worked in the Western Region Civil Services from 1950-56. Despite this progress of assimilation, there was still significant disparity, and the future favored physicians with M.B.B.S. degrees.

Dr. Ogunlesi, like his fellow L.S.M. holders, was visibly marginalized. Some were not even given medical jobs anymore. Subsequently, many L.S.M. holders found themselves in Ireland, Edinburgh, and Scotland and could take the M.R.C.P. examinations, but not that of England. Somehow, Ogunlesi, a gifted physician, secured a training position in London and subsequently became the first African to take and pass the M.R.C.P. examination of England in 1958, a move that qualified him as a specialist.

On arrival in Nigeria, he was given a job as a Medical specialist at Adeoyo Hospital, a teaching affiliate of the new University of Ibadan Medical School. He worked diligently and tirelessly to keep up and demonstrated competence like the M.B.B.S. holders. He got noticed by Professor Alexander Brown, the founding Head of the University of Ibadan Department of Medicine. At the time, his Department was full of mostly British expatriates, all with M.B.B.S. degrees and prolific researchers regularly publishing in peer-review Journals in direct competition with the University of London Department of Medicine.

As fate, hard work, diligence, and luck would have it, a position opened up in this high-power academic, British-expatriates-dominated Department in 1961. Although there was widespread discrimination against the L.S.M. holders, and the unwritten policy was to keep them out of the new University program, Professor Brown saw an exceptional talent in Ogunlesi and gave him a chance. Recognizing the potential difficulty the Young Ogunlesi would face in this high-pressure, highly-competitive position, he put him under his wings as he groomed him in this stiff academic setting. At the time, his faculty included world-renowned Cardiology professors like Professor Abrahams and Professor Parry. Other highly-regarded faculties in the Department included Professors Kinnear, Low, Monkosso, Harman, and Ball. However, Dr. Ogunlesi did not disappoint. He continued excelling, satisfying his boss, and performing his duty above and beyond expectations. Thus, Ogunlesi became Professor Brown’s right-hand man and next in line. In this post-independence period, indigenization was gaining popularity. The need for British citizens heading Nigerian’s parastatals was waning. The Indigenous Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ibadan was named, and the British VC relinquished power; this trend was happening nationwide.

Dr. Ogunlesi continued to be diligent and exceptional, performing creditably, and was now positioned next to Professor Brown. As fate would have it, the young, dynamic founding Chairman of Medicine, Professor Alexander Brown, died suddenly of cardiac arrest. Subsequently, all these Expatriate Professors in the Department unanimously voted to promote Ogunlesi to full Professor, making him the first Nigerian Professor of Medicine. He later served as the first Nigerian Head of the Department of Medicine from 1969-72.

- Advertisement -

As Emeritus Professor, he gave a tutorial to our class in 1985 as new clinical students at U.C.H. My classmates still remember him drawing a futuristic map on the blackboard, which looks like the current electronic medical records of 2023. He was smart, with a brilliant mind and longitudinal foresight.

He was a great clinician, an astute scientist, a doctor of doctors, and a teacher of teachers.

May the Good Lord continue to rest his soul. Amen.

Abraham A. Ariyo, MD, MPH, FACC.

Director, HeartMasters Cardiology,

Interventional Cardiologist, Baylor Scott & White Medical Center.

- Advertisement -